This past month has seen little action on the Bond 26 front, after a flurry of news and announcements in the spring. New producers Pascal and Heyman are busy in London, presumably meeting with writers and possible directors.

Whilst the film side of the franchise is publicly quiet, the literary side has been stepping up to fill the void with several announcements and releases. The next year will be busy for Bond readers:

Talk of the Devil - The Collected Writings of Ian Fleming (out now)

Felix Leiter in The Hook & The Eye by Raymond Benson (the first four chapters are out now)

The Solider & The Chistmas Tree by Simon Ward (September 2025)

The Q Mysteries: Quantum of Menace by Vaseem Khan (October 2025)

Double-O Trilogy Book 3 (untitled) by Kim Sherwood (2026)

Kim Sherwood’s third and final book in her Double-O trilogy being pushed to 2026 is a bit of a surprise considering it is understood it has been written for some time now.

With all of this buzz around Ian Fleming’s literary creation, we pondered the cultural importance of his work in 2025.

Fleming’s Relevancy

The morning had the sharp smell of espresso and double-decker bus exhaust. Somewhere in London, a civil servant pulled on his vape for the first time that day and opened 'Casino Royale'. In a Tokyo metro, a student annotated 'You Only Live Twice' in red ink. And on a beach in Jamaica, a collector weighed the spine of a first edition 'Moonraker' in his hand like a priest with a relic. The rituals of reading Ian Fleming persist - not for the faint of heart, but for those who, like Bond himself, prefer their realities shaken, not stirred.

The world of James Bond, in 2025, lives on in a curious half-light. The man is a relic; the myth is immortal. Where once readers sought escape from ration books and Khrushchev’s sneer, today they turn to 007 for something different - less consolation, more confrontation. The novels are scrutinized now, as well as savoured. The black and white world Fleming drew in his short, savage prose is tinged with discomfort under the fluorescence of modern values. And yet, the Bond of the page endures - still elegant, still brutal, still magnetic.

There was a time - easier to recall in the clarity of a gin martini - when Britain still thought of itself as the centre of the world. It was 1953. The Queen was new. The Cold War was not. And into this simmering, shell-shocked landscape stepped a man named Bond.

Fleming knew exactly what he was doing. A former naval intelligence officer who wrote from a desk in Jamaica, he crafted James Bond not for England as it was, but as it wished to be. Dangerous, worldly, and never late for dinner.

Post-war Britain needed a myth. The Empire had shrunk. Food was still rationed. And behind every polite cup of tea lurked the thud of Soviet boots. Bond, with his Bentley, his Morland cigarettes, and his license to kill, was the answer. He was Britain’s dark mirror - suave, ruthless, imperious. He moved through Fleming’s pages with the ease of a ghost trained in Savile Row and blood.

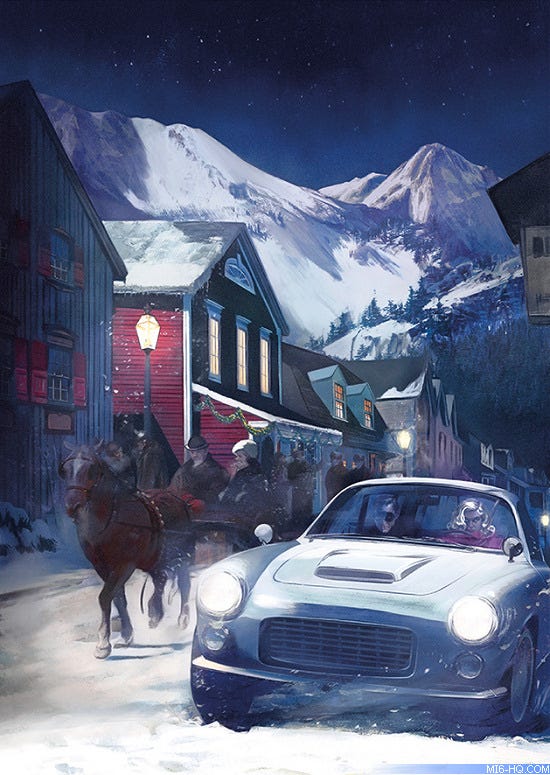

But it wasn’t only Bond that mattered. It was the world he moved in. Fleming’s novels made theatre of geopolitics. 'From Russia With Love' introduced SMERSH as a bureaucratic phantom of dread. 'Dr No' set the Caribbean bubbling with menace. The villains were grotesque, the plots theatrical - but beneath the surface, Fleming was sketching a real-world anxiety from his golden typewriter.

Bond was not the last gasp of the Empire. He was its hallucination.

The appeal, if we are honest, was not subtle.

Fleming wrote for men who liked their eggs just so and their women mysterious. And he wrote fast. The plots clicked like clasps on an attache case. The prose was brisk, brutal, and laced with sensual precision. He knew what men wanted. A good fight, a bad woman, and a better drink.

And yet there was more. In Bond’s world, everything meant something. A cigarette was a smouldering fuse. A casino game was a war. A kiss might as well be a confession. Fleming made ritual of danger - and danger, like glamour, never goes out of style.

He gave his readers what the world could not: certainty. Villains were evil. Guns killed. Seductions succeeded. Every narrative ended in either pleasure or punishment. This was espionage as opera, masculine anxiety wrapped in mohair suits.

Even the coldest hearts felt the heat. 'Casino Royale' begins with Bond, sleepless and suspicious, sniffing the sweat and fear of a casino at 3 a.m. - “the scent and smoke and sweat,” as Fleming puts it, becomes “nauseating”. And yet Bond remains at the table. Of course he does. He’s James Bond.

The novels appealed because they offered escape wrapped in danger. They were not safe. They did not pander. They lingered long after the last page like a bruise you didn’t know you wanted.

They were, in their time, exactly what their time required.

But it is no longer enough to thrill. One must explain oneself.

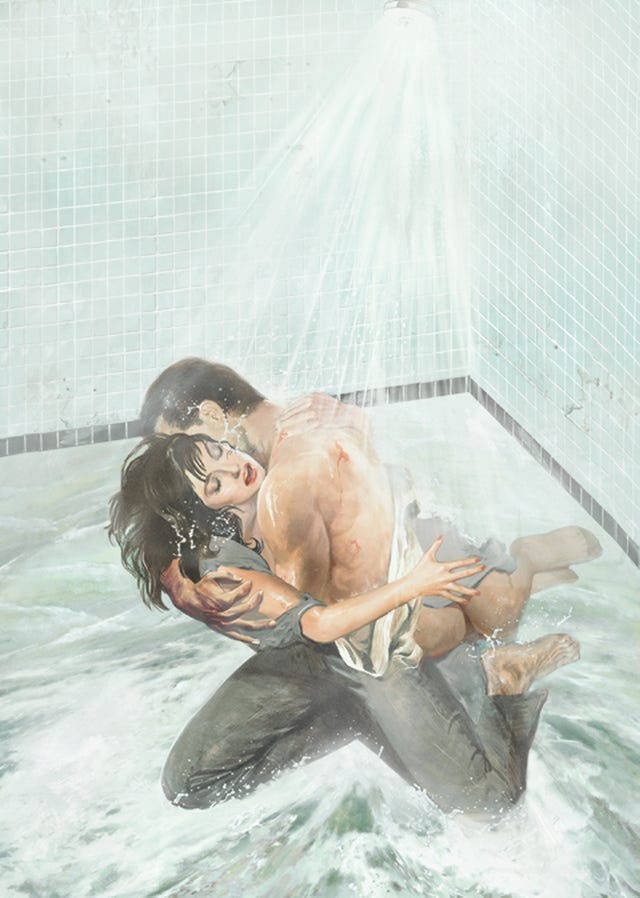

The women, for instance. Vesper Lynd - beautiful, doomed, and carved from melancholy - remains enigmatic. But others? Solitaire. Honeychile Ryder. Tiffany Case. Each drawn with the same cocktail of eroticism and pity. Critics and academics today wince. Bond’s charm is studied now with a scalpel. His tenderness, when it appears, is fleeting and transactional. 'The Spy Who Loved Me' attempted to let a woman speak, and the result, for many, was the strangest of the series: half confession, half cautionary tale.

Then there are the darker geographies of the novels. Jamaica in 'Live And Let Die', Harlem in the same. The scorpion under the thorn bush in 'Diamonds Are Forever', crushed under a muttered racial epithet. It was all “of its time,” his defenders say - but the phrase no longer comforts as it once did. Fleming’s love of foreign places was real, and so was his imperial instinct to control them. In 2025, that contradiction breathes heavily through every page.

Still, the novels do not apologise. They do not try to please.

So why read Bond now?

Because no one else wrote about death and desire quite like Ian Fleming. His style - lean, tactile, unhurried - cuts through time. A hand resting on the butt of a Beretta. The slow exhale of Morland smoke. The taste of a soft-boiled egg dusted with black pepper. Fleming’s world is artificial in the best sense: curated, deliberate, mythic.

Bond is the blueprint. Every spy novel that followed carries Fleming’s watermark, even the ones that detest him. John le Carré wrote in reaction, but not in ignorance. Jason Bourne, George Smiley, even Ethan Hunt - they exist because Bond taught us that spies could be seductive and lethal, half soldier and half satyr.

Modern readers return not only for the thrills, but for the geopolitical history disguised as pulp. 'From Russia With Love' reads like a primer on Soviet psychological warfare. 'Thunderball' predicts the privatization of terror long before we had names for it. Bond’s villains, often grotesque exaggerations, now feel eerily close to life: oligarchs with gold fetishes, technocrats with private islands, former spies turned anarchists.

Fleming’s Bond novels are no longer pulp. They are primary sources. Students of the Cold War can read them as case files. Writers dissect their rhythms. The general reader, especially the disillusioned one, finds comfort in Bond’s certainty. He knows who he is. He kills when he must. He regrets just enough to be human, never enough to be paralysed.

And the books sell. New editions emerge with introductions that try to explain away the inconvenient truths. Annotated versions. Graphic novel adaptations. Audiobooks narrated by actors born long after Fleming’s death but clever enough to imitate the cadence.

Bond survives not despite critique - but because of it. To read 'Goldfinger' in 2025 is to engage in cultural archaeology. You do not have to admire everything you uncover. But you will feel something. And that, in literature, is rare.

James Bond is no longer a mirror. He is a monolith. And like any monument, he attracts both veneration and vandalism. Ian Fleming, with his exacting prose and morbid glamour, did not intend to write timeless fiction. He wrote for a world on the edge of its nerves - a world of cigarettes in train compartments and nuclear countdowns.

But fiction, like espionage, outlives intention. The world turns. And yet Bond remains.

Still smoking. Still watching. Still relevant.

Listen

If you apply the 'Death of the Author' theory to the James Bond books, what are you left with? For this episode from the archives, the panel delves into the concept of 'Death of the Author' in the context of Ian Fleming's James Bond novels. Is it now practically impossible to read the books independently of the bias created by the reader's knowledge of Fleming? If you remove the author from the reading of the text, is there any objective meaning left? Has Fleming become Bond rather than Bond being based on Fleming? Why did the literary estate start with this concept and then double-down on a reversal in 2008? Warning: the feelings of some continuation authors may be at risk.

Watch

Author Raymond Benson has recorded the author’s note and opening chapter to his new Felix Leiter adventure ‘The Hook & The Eye.’

Exit Through The Gift Shop

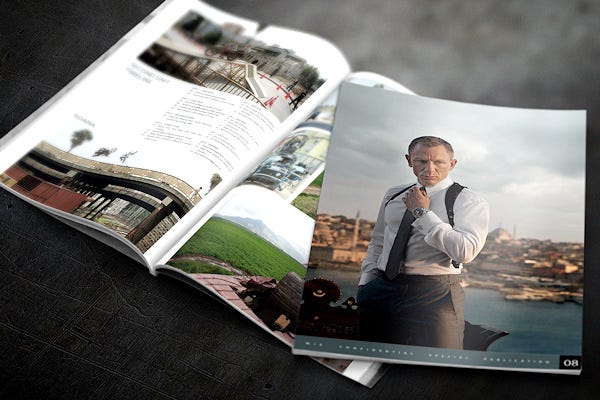

There are still a few copies of our 100-page limited edition publication ‘Skyfall: Production Diary’ available.

Season 19 of MI6 Confidential will be launching in the next couple of weeks, so be sure to grab this and any other recent magazines you may be missing, as there is always a run on back issues when we launch the new subscription.

More Bond

In need of some daily 007? Check out our other outlets:

Hmm... I would have liked to hear some thoughts on "Talk of the Devil".